I have a story to tell my fellow conservatives. I went to a strange land, saw and learned much. And now I must report back.

After sixteen years working in politics and media, my life took a detour. Laid off from my last office job, discouraged, adrift, I went to work at a restaurant — and discovered a parallel universe. Delivering pizza for places like Papa John’s and Domino’s, I found myself immersed in the blue-collar service world of high school-educated Americans, immigrants, (mostly Hispanics and Muslims from North Africa and the Mid-East), and young people on their first job.

Over the years, I worked with hundreds of people in six high-turnover restaurants. I now drive part-time for Uber and Lyft (over 10,000 trips) while I study web design.

This world was so different from my upbringing, my schooling, and my suit-and-tie jobs that it was like moving to a foreign country, right here in Falls Church, Virginia. I had restaurant and construction jobs when I was young, but as an experienced middle-ager, this detour had a profound effect on me. My stories and observations could fill a book, and indeed someday I’ll finish my memoirs (Deliver Me From This: Confessions of a Pizza Guy).).

A Parallel Universe

My chief discovery was how much of this parallel universe is hidden and separated from more affluent, white-collar people. And in turn, the people I worked with in these low income, low status jobs, outside the knowledge economy, are largely disconnected from and uninterested in the world of elites. It is difficult to convey how removed their sources of information, news, and opinion are from yours (I’m assuming by virtue of you reading this).

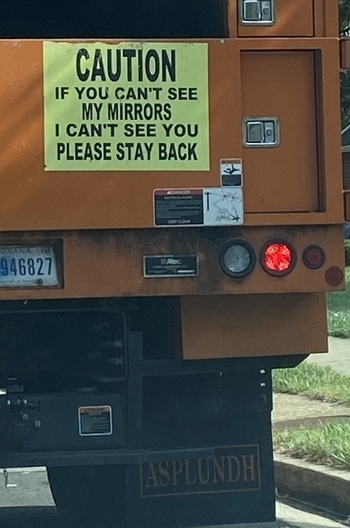

These classes of people don’t often truly “see” each other. An analogy: you’re driving down the highway behind a big truck, trying to figure out when it’s safe to pass. Then you note the truck’s sign: “If you can’t see my mirrors, I can’t see you.”

We don’t see them, so they can’t see us.

This separation of the classes I witnessed along economic and social lines, and reflected in diverging rates of indicators like divorce and church attendance, is bad for everyone. It’s bad for the country.

In Coming Apart, his 2012 study of this divide, Charles Murray warned of:

... [A]n evolution in American society... leading to the formation of classes that are different in kind and in their degree of separation from anything that the nation has ever known... [T]he divergence into these separate classes, if it continues, will end what has made America America.

Two groups of people I encountered in particular — immigrants adapting in a fractured America, and people falling through these fractures — are experiencing a void at the center of today’s America.

Immigrants encounter a country increasingly divided over identity and assimilation, its founding principles, and even its own history. Often coming from more traditional cultures, most of the immigrants I came to know arrived eager to work for their American dream, but sometimes expressed deep misgivings as to America’s soul. Stripped of its founding principles and supporting virtues, American wealth, power, and influence can seem like an arbitrary get-rich-quick scheme.

Meanwhile, the void is swallowing a growing number of downscale, largely native-born Americans. They are disconnected not only from elites, like many working-class folks, but increasingly from traditional sources of identity, meaning, and community, chiefly family and traditional religion. I saw them regularly, often young men, drifting through these restaurants, from no place in particular, and pretty much going nowhere. Theirs is a world with no roots and no horizon.

This Is Not Politics

I’m not calling for a political effort aimed at these folks, at least not in the traditional election-time “outreach” drive. This is long-term and does not meet the demands of the political calendar. But this is not charity, either; I’m not trying to waste your time preaching the novel idea that the rich should help the poor.

Rather, I am appealing to your self-interest: If you like your America, and you want to keep your America, we must find better ways to fill the void.

The vacuum of identity and history is being filled, of course, by the public schools and pop culture. In so much of our public life we have been slow to grasp this: We cannot rely on increasingly liberal institutions for conservative ends.

These two groups — newcomers entering the mainstream of American life and the alienated slipping away — are among the most difficult to reach with a conservative or traditional religious message (outside of a church or mosque), whether through top-down organizations or social media. We can’t be content to merely project our beliefs via various communications channels. There is no shortage of apps. There is a shortage of personal and available social capital.

Opportunity Centers

The most practical ideas inspired by my detour involve immigrants. If we want newcomers to assimilate, we need to be directly involved in that process. If we help them accomplish their goals of getting a job, learning English, and becoming a citizen, we will then be in a better position to share with them a love of America for all the right reasons.

In Who Are We?, Samuel Huntington wrote of the “major social movement” around the turn of the last century which inspired many civic organizations focused on assimilation, patriotism, and citizenship for that era’s large wave of immigrants. We need similar innovative efforts to help today’s many newcomers.

Mark Krikorian of the Center for Immigration Studies, a restrictionist, has suggested establishing neighborhood American Opportunity Centers to teach immigrants English, preparation for the citizenship test, and practical skills like doing your taxes and establishing good credit. “Even more important,” says Krikorian, “Opportunity Centers would connect grassroots volunteers to immigrants, allowing each to see the other as they really are . . .”

Note the emphasis on seeing.

Another way to establish a neighborhood presence would be to emulate Easy English News, a monthly newspaper aimed at new English speakers published by Elizabeth Claire, a retired teacher from New Jersey.

I saw this little paper passed around at places like Papa John’s. Each issue contains brief news articles, some practical vocabulary lessons, history features, a crossword puzzle. It’s well-written and the issues I read had no discernible bias.

Conservatives need to launch a printed publication like this and make it available for free in news boxes around subways and bus stops, right next to the Washington Hispanic, the apartment guide, and the alternative newspaper. Bulk copies could be made available to schools, churches, and other groups.

A print publication can reach nooks and crannies its own website might never find. Ideally, the newspaper would be published by a neighborhood organization, mutually strengthening their local presence.

We Need To Show Up

In my experience, immigrants have a natural curiosity about their new country. We should respond with the story of how and why America came to be the country they wanted to come to. Conservatives should be eager to tell this story to newcomers, and explicitly invite them to help keep a good thing going.

We should neither romanticize nor condescend to these folks. And of course, much of the work necessary to fill the void is low status and low pay. For what it’s worth, I found it extremely rewarding to train new delivery drivers, helping them learn their job and start earning tips as soon as possible. I saw how a little help goes a long way in the trenches, and why Woody Allen said “90% of life is just showing up.”

A void in my life took me on a detour. Along the way, I encountered another void, way out there, on the other side of the counter at your local restaurant.

How do I know there’s a void? Because Maher, an older guy from Egypt, told me so: “I ask many American for help my English. Most no help me, too fast, but you — you different.“

So then there was a something, where before there was a nothing.

For both of us.